2024 hurricane season: a look back at a busy year

The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season had an above-average number of storms. Find out more about hurricane resilience.

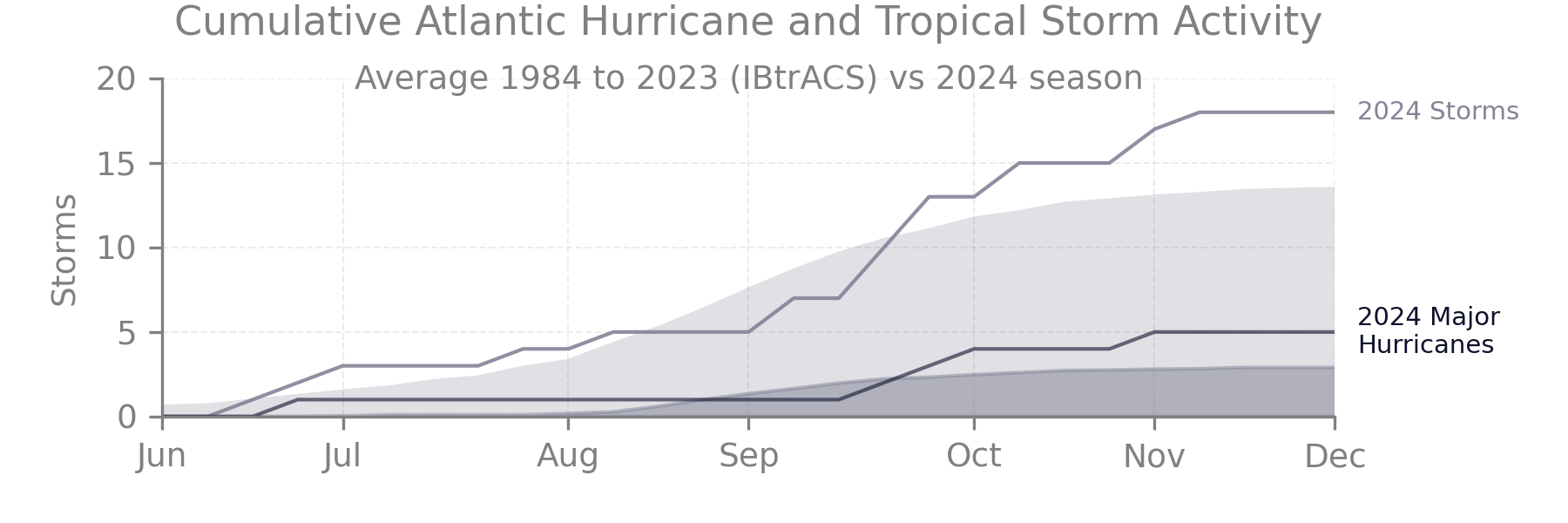

The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season got off to a slow but significant start, fell into a lull, and ended with a series of storms that were by turns devastating and unusual.

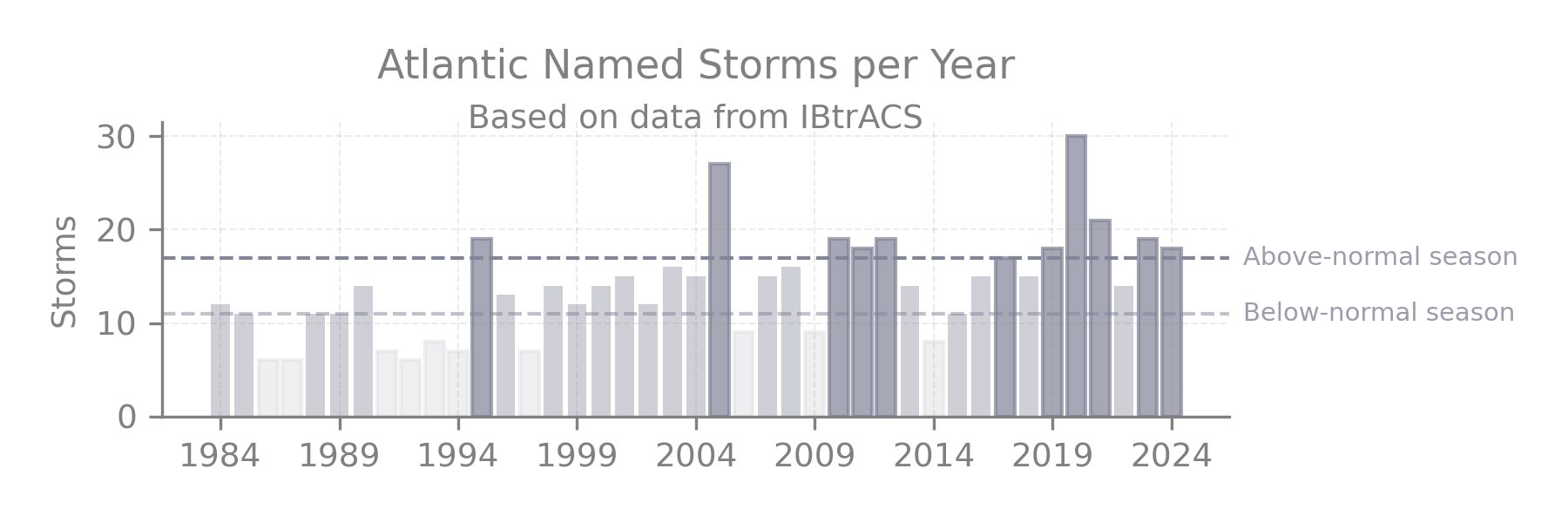

Though the total of 18 named storms in 2024 is above average, it falls short of extremely active years like 2005 and 2020.

With the 2024 season ending on Nov. 30, a team of researchers at FM, led by Research Director of Climate Risk & Resilience Dr. Angelika Werner, is poring over data to develop key takeaways and resilience lessons. Here are some of their early observations about the 2024 season:

An early start, and then a lull. What happened?

The pre-season forecast from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) was stark: Record warm ocean temperatures and an expected shift from El Niño to neutral/La Niña conditions created a favorable environment for an active hurricane season. And just a few weeks in, the season got off to what NOAA called an “explosive start.” Hurricane Beryl was the earliest Category 5 hurricane in the Atlantic basin on record.

But then, for several weeks, the Atlantic hurricane season fell into a lull. From Aug. 20 to Sept. 8, there was no storm activity at all. Researchers are still trying to determine why exactly, but a mix of drivers emerge. The two strongest:

- A strong North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). This signal, normally most active in autumn and winter months, is categorized by the pressure difference of the stable patterns of the Iceland Low and Azores High pressure systems. During this year’s summer period, the strong NAO pushed cold and dry surface air from the north directly into the main development region of tropical storms in the tropical Atlantic and added vertical windshear, both of which suppressed convective activity.

- A northward shift of the West African Monsoon, also meant a northward shift of related thunderstorm activity that often serves as seeds of tropical storms when they move from the African mainland into the Atlantic Ocean. Now those systems encountered cold, dry and windshear conditions that prevented any further development into tropical storms.

“It was really spectacular, how long the inactivity lasted,” Werner said.

The lull, though, didn’t last forever. The ingredients for an active season were still very much in place, after all, even if other meteorological factors were temporarily pushing against them. On Sept. 26, Hurricane Helene made landfall in Florida as a Category 4 storm, then swept up through the southeastern United States. On Oct. 9, Hurricane Milton hit Florida as a Category 3 storm.

The 18 named storms in 2024 were more than the average year over the last three decades of about 14 named storms.

- The busiest year on record was 2020, with 30 named storms, according to data compiled by Colorado State University.

- Just before the season started, NOAA’s forecast had predicted 17 to 25 named storms this year. So 2024 was generally in line with that forecast.

The key takeaway: Forecasting is hugely important. But it can only tell you so much. A resilience mindset means preparing for the storms even when you’re in a lull.

‘Rapid intensification’ of Hurricanes Beryl, Helene, Milton and more

Some of the notable storms this year, including Beryl, Helene and Milton, intensified rapidly. Researchers are continuing to study whether this is a trend, and if so, whether it will continue, Werner says.

If the trend bears out, it brings a new set of challenges – including less time for communities to prepare. Dr. Leandro Masello, climate scientist at FM, has been studying this phenomenon: “Overall, there is a global trend indicating that these events are becoming more frequent, although the trend is less pronounced in the North Atlantic basin. It is important to note that most major hurricanes undergo rapid intensification at some point in their lifecycle, and these storms tend to intensify faster than they used to.”

Added Werner: “We also see an increase of rapid intensification shortly before landfall, which makes warning impacted communities and sites tremendously difficult.”

The key takeaway: More research is needed on rapid intensification – which puts preparedness in the spotlight.

A variety of perils, from rain to tornadoes

The size of a particular storm and even where it hits clearly play a major role in how much damage it causes. But there are plenty of other variables, too. One is how unusual the storm’s features are for a given area. Heavy rains can be much more damaging in an area that doesn’t usually see them. Same with tornadoes that hit areas that are not accustomed to them.

That was on display during the 2024 season, particularly Hurricane Helene. A few days before Helene, a totally separate weather system drenched the south with rain leaving soils in the region completely saturated. Helene added about the same amount of rainfall on top with no capacity of the ground to absorb any of the water. The area was not accustomed to that amount of rain, intensifying the property damage. Across the 2024 season, rain was a key driver of storm impacts in affected regions.

Hurricane Helene and Hurricane Milton, meanwhile, both spawned tornado outbreaks in areas that aren’t well prepared for them. It’s not unusual for hurricanes to lead to tornadoes, but none of the current risk models take them into account, according to Werner.

The wide variety of perils in 2024 highlights the need to expand emergency drills and education about the potential impacts to new areas, Werner said.

The key takeaway: As the climate changes, expect the unexpected.

Climate change impacts on hurricanes

The climate is changing, and the frequency and severity of some risks are changing, too. The flooding that your grandparents only experienced once in their lives might happen to you three or four times if you’re unlucky, Werner says, an observation that goes beyond just hurricanes and extends to things like the devastating floods that recently occurred in Spain.

“You may think of the changing climate as loaded dice,” Werner says. “We observe events that always have been possible, but the likelihood of occurrence has shifted.”

How exactly climate change will modify the nature and frequency of hurricanes isn’t fully clear yet. But warmer oceans are creating conditions for bigger – and potentially more dangerous – storms. Warmer water means storms can intensify more easily and quickly once a small convective system has formed. In combination with warmer air these systems can hold more moisture leading to stronger tropical cyclone-induced floods. And sea level rise adds to the risk of coastal flooding.

The key takeaway: Climate change requires more research, as well as extra vigilance.

Resilience is possible

The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season was more active than usual. But there are steps that clients – and any business – can take to address those challenges.

That includes:

- Heed warnings well ahead of impact, get protection against wind and flood in place and drill staff for the right emergency response.

- Building natural hurricane protections to knock down storm surge, like stone, coral or plants.

- Creating a “sacrificial” first floor free of expensive equipment that would be damaged in a flood.

- Looking carefully at vulnerable coastline areas when acquiring new facilities or getting rid of old ones.

- Working with neighbors on places to pump water in the event of flooding and rain.

- Consulting the latest FM Approved solutions for wind, water and floods.

- Checking roof drains to make sure they’re clear of debris and testing emergency generators.

“With many of the things, it’s education,” says Werner. “Education and training.”